Quest for peace in Kashmir throws up debate

14-June-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 24

Last week, the Government of India decided to make public the report by the interlocutors it had appointed to visit Kashmir and listen to people’s views about peace and conflict.

It did so seven months after the report had been submitted, and with a disclaimer that: “The views expressed in the report are the views of the interlocutors. The government has not yet taken any decisions on the report. Government will welcome an informed debate on the contents of the report.”

|

|

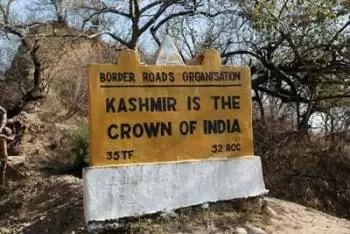

There is a suggestion to create Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh into three separate regions (Photo: Infochange News & Features)

|

The delay and the distancing have ensured that what would always have been a sceptical reception for such a report was actually quite a cold one.

Predictably, many of the criticisms have been about the interlocutors’ suggestions for re-distributing authority within the state. The suggestion to divide Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh into three regions has drawn criticism, for instance; it is argued that minorities will be created and isolated within each of the regions.

There are concerns expressed by other communities that they will be overlooked, and within each region there are some for whom this is not enough.

For instance, some groups in Ladakh want union territory status rather than a separate regional council. The interlocutors compare the powers enjoyed by the governments of POK/Azad Kashmir and Jammu and Kashmir and find the Indian state is better off.

They suggest that central laws applied to Kashmir after 1953 be reviewed, but anticipate that most will be found innocuous and even useful.

There is no way for such a report to please everyone; in fact, the mandate given to such initiatives is quite thankless, and far from facilitating consensus the results often unite people in their displeasure. There is also some debate about whether any resolution is possible without Pakistan, while the interlocutors recommend going ahead with or without Pakistani participation.

Re-distributing authority is one of the key demands and most common solution to any conflict situation. And intrinsically, any re-distribution of power, territory and authority engenders at least one, if not multiple, mirror-demands.

There is a magic moment in the political life of every community at which its aspirations could take a territorial turn, if the community is concentrated in one region. Democracy has the potential to absorb the demands and respond to the aspirations of people before that magic moment comes -- cultural rights, good governance and responsive politics help.

Many a time, grievances and aspirations can be dealt with through administrative remedies, creation of services and even symbolic gestures such as the re-naming of a street or the issuance of a stamp. But when those smaller measures fail to happen, the political leadership of the community often chooses to demand that a territory be demarcated within which they can make their own decisions.

The point is that responsive governance, indeed national integration, requires a constant re-negotiation of the contract between a state and its peoples.

Indian politics is actually a great example of this. We focus on moments of violent intransigence and we focus on the vulnerabilities that we see, but the reality is that the fabric of the Indian state has survived by constant internal adjustment.

The traumatic experience of Partition made the Constituent Assembly really anxious to ensure there was no room for further vivisection of the country. For every decentralising measure, there was one that tied the units of the Indian state closer to their centre.

When functional areas were distributed between the Centre and the states, residuary powers were vested with the Centre. And Emergency provisions, inherited from the colonial state, turned India into a unitary state for the duration of the Emergency period.

Nevertheless, like states around the world, India too has systematically and constantly engaged in the re-distribution of authority across political and administrative levels. This includes both centralising and decentralising changes and a re-distribution that may be functional, political and/or territorial.

In spite of the immediate allergic responses by the political elite and op-ed writers to polemical demands of autonomy, the Indian polity has frequently re-drawn lines and devolved authority as a way of accommodating the endless tide of demands and grievances it receives.

Re-distribution of authority within the Indian state has taken the form of re-organising states -- on the basis of language and other identity, as well as on administrative grounds; of creating conventions that safeguard against the misuse of centralising provisions; of devolving power to local government and through amendments in the power-sharing between Centre and states.

Even in the shadow of Partition, the Indian Constitution was set up as a ‘Union of States’ -- a federation, albeit one with a strong Centre. Amendment of these provisions to create, re-shape or re-name units was made relatively easy, as also the movement of functional authority from one level to the other.

Even at the moment of its commencement, the Constitution’s Article 370, written to accommodate the unique circumstances of the accession of Jammu & Kashmir to the Indian Union, set the precedent for a wide range of other such accommodations.

The 371 series of provisions now covers Maharashtra, Gujarat, Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh and Goa -- each article creating special arrangements for the state -- some involving centralisation, some decentralisation, some internal arrangements.

It is also important to note that the demand for greater autonomy for states has come from across the Indian polity, not just states with insurgencies. State governments have time and again expressed the need for greater financial independence from the Centre and for freedom from political interference.

The Dravida movement offers an unusual instance of a movement that moved back from secession to statehood and into the mainstream of national politics. Once the DMK won the 1967 elections in Tamil Nadu, they set up the Rajamannar Committee in 1969 to examine state autonomy and Centre-state relations and make recommendations for a better balance.

The committee made several practical recommendations relating to the central, state and concurrent lists; financial arrangements; the setting up of an inter-state council; the appointment and role of the governor.

The Centre’s response was that these had already been suggested by the Administrative Reforms Commission. A period of increasing central interference in state politics followed. In the early-1980s, a series of meetings by non-Congress chief ministers, including Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir, forced the government to appoint the Sarkaria Commission to go back over the same ground as the Rajamannar Commission.

The Sarkaria Commission’s recommendations were a little more conservative, in that it remained in favour of a strong Centre while speaking of ‘cooperative federalism’.

One lasting consequence of this climate of collective state bargaining is that the once-rampant abuse of Article 356 to topple state governments is now virtually extinct. Even as regional parties and leaders are now indispensable to political formations at the Centre, the old complaints remain -- stingy or biased resource allocation to the states, lack of understanding of local needs and a Delhi-oriented national politics.

States seek greater autonomy from the central government, and union territories seek statehood, and communities within states seek their own districts, autonomous councils and other forms of representation and self-government.

In northeast India, virtually every peace accord has resulted in the creation of new units or new agencies (or usually both). They range from full-fledged states (Nagaland and Mizoram) to innovative new administrative arrangements within or across districts: Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Councils, Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council, Bodoland Autonomous Council and, later, Bodoland Territorial Council, Sinlung Hills Development Council and autonomous councils for the Karbi-Anglong, Rabha-Hasong, Tiwa and Mishing.

The result is that the simple pyramidal depiction of the Indian federal system that we learn to draw in school, in reality looks more like a tie-and-die fabric, with colours and jurisdictions bleeding into each other. And that’s as it should be.

Centrifugal and centripetal impulses play out in tandem in the politics of every nation-state. No single arrangement is a final resolution, and no sooner is one negotiation done than another one must commence.

Nation-building and preserving the nation-state community are about staying this course that is facilitated by dialogue and vitiated by the use of force (by any side), with patience and a willingness to listen. It is a process of many new beginnings and constant course-correction, and needs participants to remember that the journey is what is real -- the destination is a dream. - Infochange News & Features