Post-retirement soldiers still wage battles of a different kind

29-June-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 26

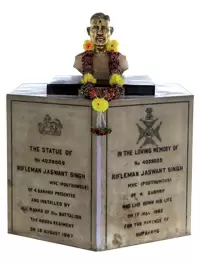

For connoisseurs of the 1962 Indo-China border conflict, the name of rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat is etched in stone, quite literally in Arunachal Pradesh's Jaswantgarh.

In an otherwise dismal performance by an under prepared Indian Army and even more under prepared political leadership, Jaswant Singh stands out as a beacon.

|

|

War hero Jaswant Singh’s aged mother is yet to get the land allotted to her martyred son (Photos: The Sunday Indian)

|

While it is mandatory for every officer and soldier posted on the Indo-China Line of Actual Control (LOAC) to pay tribute at Jaswantgarh – the site of a heroic standoff between the rifleman and advancing Chinese troops near Tawang –the actual story of what happens to a soldier's family after death or disability is a sordid tale of wrangling, neglect and utter official apathy.

Five decades after the war, the soldier’s frail mother continues to fight for a piece of land which was allotted posthumously to her son. The case has reached the Supreme Court and no one can quite predict how it will play out in the end.

The facts of the case run like any other land dispute – except that this involves a war hero.

Additional district magistrate, Dehradun in his remarks states, “Leela Devi, mother of Shri Jaswant Singh Rawat who was martyred during the Indo-China war was allotted 1.48 acre land in Raipur.

“Out of this, 1.08 acre has been allotted to her but 0.40 acres land is under the possession of Umed Singh Rawat….,” a bland statement of facts which does not take anything into account except banal official modalities.

Naik Ges Bahadur Gurung is a living testimony to the way the system treats its soldiers. When Gurung lost his leg during the Kargil operation, he could have scarcely divined that his problems had just began.

The State Bank of India, Dehradun, entrusted to assist the valiant soldier, has instead ordered a recovery of Rs 3,72,506 because of a gross official mix up - his pension was increased to an amount for which he is not entitled. “Today, I am fighting a battle which is bigger than the one I fought in the mountains of Kargil,” rues Naik Gurung.

Tragically, his battle is not against an enemy but against the system which he was tasked to protect.

With three daughters to look after, his problems have compounded after SBI served a notice on him stopping his pension since August 30, 2011. In an emotional appeal, Gurung wrote to the SBI and other authorities, "I am faced with the problem of feeding my family as the bank has stopped the pension of a disabled soldier like me.”

Gurung's story is by no means new, nor is it confined only to soldiers. It also includes officers who have fought several wars for the country.

Take the cases of Signalman Hari Singh and Lt Col Virendra Kumar Choubey, both of whom are victims of gross official apathy after serving for years in insurgency-torn Jammu and Kashmir. Both continue to run from pillar to post seeking disability dues, something that is legally and justifiably theirs.

The smile of Signalman Hari Singh may camouflage his 100 per cent disability as reckoned by the Army Medical Services, but his story tells you why Indians are less and less willing to serve with the services.

Stoic Hari Singh, with the smile that comes naturally to battle-scarred veterans, says to keep the wolves away he picked up the job of a security guard at the Punjab and Sindh Bank in Dehradun.

|

“My bank had stopped my disability pension completely and I had to run to many authorities who are now working to restore status quo. I was not being paid even after repeated reminders and requests.''

The case of another war veteran, Lt Col Vinod Kumar Choubey, who served in the valley during the last decade, reveals the severe limitations that a flawed civilian-administered system imposes on injured soldiers.

Choubey was entitled for 20 per cent disability pension but had to fight for his dues. An officer like him had to take the help of the Uttarakhand Ex-Servicemen League (UESL), a voluntary organisation committed to the welfare of soldiers and their families, to get his entitlements.

If a senior officer like Choubey had to adopt this course of action, it is not hard to imagine the plight of the poor jawan or non-commisioned officers (NCOs) who are not educated enough to be aware of their rights.

Just how widespread is this problem? In order to maintain a youthful profile of the armed forces, approximately 60,000 service personnel are retired/released every year at a comparatively younger age.

At the time of superannuation, the majority of service personnel are at an age where they have numerous unfinished family and other social responsibilities which necessitates taking up a second occupation.

According to official figures, there are more than 20 lakh ex-servicemen (ESM) and about five lakh widows registered with the director general resettlement (DGR).

The ESM population is mainly concentrated in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Haryana, Maharashtra, Kerala, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu.

The DGR or Kendriya Sainik Board (KSB) is assisted in their task by various Rajya Sainik Boards (RSB) and District Sainik Boards (DSB) which are under the administrative control of respective state governments. The central government bears 50 per cent of the expenditure incurred on the organisation of RSBs while the remaining 50 per cent is borne by state governments.

The mismanagement can be gauged from the example of DSB, Maharajganj, in Uttar Pradesh. When Maharajganj MP Harshvardhan Singh tried to find out the population of ex-servicemen in his area, he was frankly told that there is no such record available. It was on his insistence that a quick, albeit unreliable, census was conducted.

Says Brigadier (retd.) RS Rawat who has been waging a lone war in search of more such cases: "There are various dimensions which come to the fore only after we go deep into the problems. There are endless numbers of war widows who live in the back-of-the-beyond areas of hills like Uttarakhand. As has been the practice, neither is the widow’s date of birth nor their names mentioned in the pension payment orders of the soldiers and this has caused a lot of problems.”

Rawat recently visited Peepal Koti and Dewal Gheshbalas in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand and identified 150 such people for assistance. Not just that, soldiers having to pay bribes to get their entitlements is a telling story of how India treats its bravehearts.

By arrangement with The Sunday Indian