Six things about Dr Binayak Sen the government will not want you to know

14-January-2011

Vol 2 | Issue 2

1. Dr Binayak Sen came out of Raipur jail in Chhattisgarh after more than two years in prison on May 25, 2009. Ravaged, a victim of fabricated evidence, branded as a Maoist sympathiser with no proof, what did he first say, moments into his freedom: "Our agenda is clear," he said after coming out of jail. "Peace, not war. Political engagement, not military violence.” This was a repeat of his stated position, that he is opposed to all kinds of violence – State repression or Maoist violence. And what did the prestigious Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore do, soon after? They honoured him with the designation of Professor of Human Rights and Medicine. He studied medicine here when he was young. The entire alumni of CMC had earlier joined with hundreds of scientists, mathematicians and doctors across India and the globe to petition for his release from prison. Indeed, 22 noble laureates had petitioned the Prime Minister so that he could receive the Jonathan Mann award for extraordinary work in the health sector. Besides, the most prestigious health journal in the world, Lancet, had editorialised his incredible work among the poorest of the poor in Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh. The Economist and The Guardian, perhaps the most prestigious magazine and newspaper in the world, backed his cause.

|

|

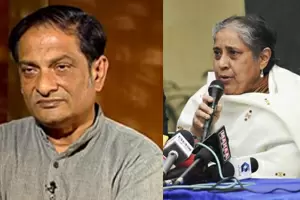

Doctor of the Masses: A crusader for public health, Binayak Sen served the poorest of the poor in remote regions of the country (right) Wife Illina has been a pillar of support to the good doctor’s service

|

2. This reporter heard him the last time in a People’s Tribunal in Delhi last summer. Soft spoken, humble and polite, Dr Sen spoke with a coherent authority because of the vast body of his work and grassroots experience. He cited a recent research study he had done with fellow scientists on the body mass index and malnourishment of people in Hoshangabad district in Madhya Pradesh. He found that under-nourishment was so widespread here, that the body mass index of the poor was less than abnormal. So abnormal that during the annual starvation months in the year, when even the minimal food supply would be choked due to economic conditions and lack of purchasing power, they would be most susceptible to epidemics and disease – malaria, typhoid, jaundice, dysentery, cardiac failure and multiple other fatal ailments. Indeed, starvation, under and mal-nourishment, and slow and sudden death are a deadly combination. Said Dr Sen: “If this is not genocide, what is it?” Ironically, there are no Maoists here. So who is responsible for this mass suffering?

3. Dr Sen started a rural health centre in Hoshangabad in 1981. The initial days in difficult conditions were the starting point of a visionary, protracted and dedicated work. Health as a socially transformative reality became the seed of this relentless work. Health as integrated to social and economic well being, women’s empowerment, education of children, and human and political rights. Health as a leap of consciousness.

4. Later, he set in motion the Shaheed Hospital at Dallirajhara, along with other doctors. He entered the magnificent movement of Shankar Guha Niyogi. Niyogi’s non-violent ‘sangharsh aur nirman’ (struggle and construction) doctrine had transformed the lives of thousands of miners and farmers in the area in terms of social reforms, wages, educational and fundamental rights. The campaign against alcohol, for clean water, and dignified shelter for the workers was a huge success. Integrated with this holistic success story was the Shaheed Hospital in this backward zone for workers, poor and local citizens, with 80 beds, dedicated doctors from across the country literally working for free, finest medical facilities with a laboratory, operation theatre and x-ray machine, and the principle that health is a fundamental right of every citizen. Soon, the hospital had satellite branches in Bhillai, Urla etc. This health movement has flowered in recent times as far as in the village of Chengail in Howrah district near Kolkata. Dr Gun, who worked with Niyogi and Dr Sen at the Shaheed Hospital, has started a modest ‘workers-peasants’ hospital with ‘people’s money and no commercial donation’ where 500 villagers every day get specialised treatment in all disciplines, including psychiatry, from specialist doctors from Kolkata, for a fee of Rs 5. No wonder, almost 100 top doctors, surgeons and medical academics in Kolkata have petitioned for Dr Sen and protested on the streets.

5. Later, Dr Sen worked in a missionary hospital, and started an NGO, Rupanter, with his wife, Illina, who is currently a professor at the Mahatma Gandhi University, Wardha. Rupantar was started with the aim of providing accessible, high quality as well as basic medical and public healthcare, across all divides. It was felt by Dr Sen that the health system is too much dependant on distant big hospitals and private clinics; that doctors and social activists should break this rigidity and move into community healthcare and wider medical knowledge systems at the local level. Rupantar trained community health workers along with fraternal grassroot workers, helped the workers enter villages, and organised local medical work in areas which had none, and where poverty was stark. There was referral, laboratory and specialised services also. In a context where most cases involved falciparum malaria, sputum-positive tuberculosis, lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea, malnutrition and antenatal care, Rupantar’s efforts became miraculous. Besides, the Bagrumnala clinic was started in the Nagri block in the district of Dhamtari in 1994. Before his imprisonment, the humble clinic has been managing patients with malaria, tuberculosis, hypertension, asthma, diabetes, and heart and kidney diseases.

6. Rupantar’s high quality medical work in the remote areas became a role model of alternative healthcare in terms of distance, value systems, social empowerment and access. The work was recognised. Dr Sen was appointed to the Chhattisgarh State Advisory Committee to advise the government on as community-based health services, health surveillance, epidemiology, epidemic control, tackling health issues among the poorest and a non-commercial and sensible paradigm of drug use.

Hence, when the BJP-led Chhattisgarh government hounds him and his family, charges him with sedition, gets him convicted with life imprisonment in what is a brazen miscarriage of justice, puts him in solitary confinement, destroys his clinic, his body of work, his body and soul, and his family’s life, future and peace of mind, is this the response to his relentless lifetime of work among the poorest of the poorest in the most difficult of conditions with no aspiration for material or wealth or fame? Is this the reward the government has bestowed to the Good Doctor?