Years after their flight from their home land, they can fight in an alien land

07-December-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 49

It is a nondescript room on the ground floor of a run-down building in India’s capital city. The lane winds its way deep inside the depths of west Delhi. The majority of refugees from Myanmar live in this corner of the city.

“Hyaaah!” a loud shout emanates from the room.

|

|

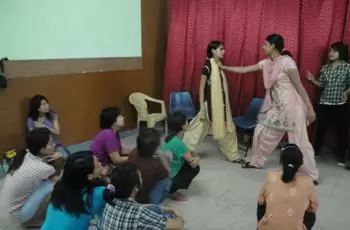

The Delhi Police conducted self defence classes for refugee women in Delhi (Photos: UNHCR/ N.Bose)

|

“Now, attack,” says a young policewoman. And the women, all refugees from Myanmar, get into position. A grab and a lunge from behind, hand on their partners’ throat and waist.

“Defend!” A deft turn, kick and they break free from their attacker’s hold, pushing with force the hands that grip their throats.

They go through the drill with enthusiasm. This group of 30 refugee women are being trained by the Crime Against Women Cell of the Delhi Police and this is a part of a ten-day training programme organised by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and its partner, the Socio-Legal Information Centre.

The issue of personal security is an important one for these women who have already gone through the trauma of displacement. “I want to protect myself,” says Ngun, a 50-year-old widow from Myanmar. “I have heard that Delhi is a dangerous place for women and that refugee women have been attacked.”

There is a suppressed anger among the women – a rage even – that is evident as they go through the training. Every move is hard fought – it is as if their frustrations are being played out through their actions and their unknown tormenters are being punished.

Delhi has the highest rate of crimes against women in India. Sexual harassment on public transport and random attacks in isolated parks are commonplace. And for many of the refugee women, it is a learning process to understand where the dangers lurk.

Taking a short cut through a park after a long day’s work seems the most natural thing to do. In the villages they came from, this was not an unsafe option. But in Delhi, many of the molestations and attacks have happened in these badly-lit and isolated areas.

Another risky place is the weekly night market. Because vegetables are cheaper the later it gets, refugees often visit markets at closing time – sometimes as late as midnight or after. There have been many instances of harassment, even pitched fights, as refugee men take on local men who harass the women from their community.

Hnem, 54, is a feisty woman who lives alone in Delhi. For her, the self-defence classes have helped her gain in self-confidence. They have also brought her new friends – she has a sense of camaraderie with her classmates. Says Hnem with determination writ large on her face, “If someone touches me at the night market, I can fight back. I feel more confident now.”

The policewomen conducting the training are constables who are trained in self-defence techniques. They have conducted events like this in colleges and schools before but this is their first time with refugee women. There are challenges. Says instructor Sunitha, 26, “They want to learn and they are learning well. But language is a problem. It takes a while for them to understand.”

The classes are in Hindi and there is an interpreter, which means everything takes twice as long. Sunitha is confident of the final outcome. “I know they will be able to do it, and I feel happy to be able to help,” she adds. UNHCR places a lot of emphasis on refugees learning the local language – in this case, Hindi.

Free classes in the language are offered to refugees and asylum seekers – children and adults – at various outreach centres in the city. Everyone is encouraged to learn. After all, without being able to communicate in the local language, even asking for help becomes difficult.

Many of the refugee women in Delhi are working hard on their Hindi, women like Khawm, 43, who lives with her daughter. Her husband was taken away by soldiers in Myanmar; she doesn’t know if he is alive or dead. Despite this trauma, she is trying to pick up the pieces of her life by adjusting to life in exile.

|

|

Constables from Delhi Poilce demonstrate an attack position

|

“I was molested once,” she says softly, adding, “We face a lot of problems in Delhi. Now if this happens again, I will be able to defend myself.” She would have liked the training to have gone on for longer – ten days, she feels, is too short. “The trainers are experts. I want to become like them – strong and confident,” she smiles.

Police constable Sharada, 26, one of the trainers, points out that a ten-day session can work wonders. “After 10 days, the confidence of these women will increase a great deal,” she promises.

The Delhi Police training team has also gained from this experience. They feel they will now be able to handle better similar training sessions that are to be conducted with other refugee groups in the coming weeks.

For these refugee women, the training represents a turning point in their lives. Years after their flight from the dangers back home, they are now ready to stand and fight back.

(The writer is an Associate External Relations Officer with UNHCR, India) - Women's Feature Service