Fear unites people of all classes in West African nations as toll rises

15-November-2014

Vol 5 | Issue 46

It’s in the air… thick and heavy… and has no antidote. Fear. Lurking in the bylanes of the poor localities, markets, playgrounds and public places, the emotion binds all classes in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea — the West African countries worst hit by the acute reality of the Ebola outbreak.

“The Ebola outbreak that is ravaging parts of West Africa is the most severe acute public health emergency seen in modern times. It has many unprecedented dimensions, including its heavy toll on frontline domestic medical staff.

|

|

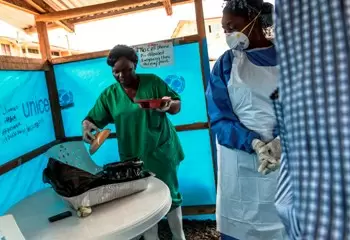

Despite fearing for their own safety, nurses working in the Ebola Treatment Units reach out to patients covered from head to foot in protective gear (Photo: UNMIL Photo/ Staton Winter)

|

“The three countries have lost some of their greatest humanitarian heroes,” said Dr Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) in her address to the Regional Committee for Africa, early November.

News coverage just cannot do justice to the commendable and courageous efforts of the nurses and other frontline health workers at the numerous Ebola Treatments Units (ETU) and Ebola holding centres that have been set up across the region.

In Liberia, the epicenter of the disease, 296 health care workers have been infected on a national level and 123 have died, as of late October 2014, according to the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW). It is said that about 35 per cent of health workers, who died in the country, could be female nurses.

“I am scared of being pricked by a needle when establishing the IV (Intravenous) line for an Ebola patient,” admits nurse Ariana, 40, working in Lower Margibi County at the Dolo’s Town Health Centre, a government facility. “It’s a challenge to insert a cannula and get a drip going …most patients are restless and confused. It’s risky, particularly when the patient is vomiting. But an infusion is necessary,” adds Lisa, 50

Seven years into the profession, Prayer, 30, is at the EIWA-3 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-run ETU in Montserrado. Her greatest dread is taking blood samples, as she fears infection. At the ELWA-2 ETU in Paynesville City, Monrovia, nurse Jernora, 35, too, worries for her health when caring for a combative patient.

Despite the fear, concern for patients’ health and wellbeing remains top priority. In fact, several nurses feel that the biochemic personal protective equipment (PPE) that they wear for their own safety comes in the way of reaching out to patients at an emotional level.

At the Island Clinic, a private health facility refurbished as an ETU by the MOHSW with support from the WHO and other partners, nurse Shelia, 35, talks of the human touch, “When patients come into the ETU, they immediately think that they will die. Their minds are completely set: death is coming. As a nurse, I have to do a lot more than providing medical care... I talk to the patients, making them believe they can survive…. I have to give them hope.

Covered from head to foot in protective gear, Hannah, 50, a supervisor at a Liberian Ebola holding centre, where patients are temporarily kept before moving to the treatment centre, explains, “ It is difficult to counsel patients and their families when they don’t know who is talking to them from within the biochemic suit.”

Adds Anna, 34, at the ELWA-2 ETU, “The PPE is difficult to breathe in. When used for over 30 minutes it can get suffocating. Counselling patients is anyway difficult because they see being treated in isolation as a death sentence.”

Despite the PPE, the thought of contracting the disease is traumatic. “I am always afraid. I place myself on 21 days (incubation period - from infection to onset of symptoms) each time I treat an Ebola patient. Who will look after my family if I die?” frets nurse Teta, 47.

Sadly, even prior to the Ebola days, nurses, considered amongst the poorest paid professionals in Liberia, struggled to make ends meet. Being healthy is essential to being able to put food on the table. Earning a paltry average monthly salary of US$ 280, far less than that of a school teacher, for them the unfortunate refrain is: take pay today and borrow tomorrow. One can only imagine the plight of the orphaned families of health workers lost to Ebola.

According to George Poe Williams, Secretary General, National Health Workers' Association of Liberia (NAHWAL), “Death benefits of health workers who died due to Ebola should be paid via an assurance company and NAHWAL should be notified of all payments made. The hazard pay must be done directly by the donor or by a designated agency out of government to make sure that those who are legitimate get timely payment.”

For those who survive, the battle may be long drawn on account of social stigma. As per the recent Madrid Declaration on Nursing and Ebola, of the International Council of Nurses, nurses perform 95 per cent of direct care of Ebola virus disease (EVD) patients and special attention must be paid to factors that might help to fight the stigma attached to these professionals.

Nasma, 43, at the ELWA-3 MSF ETU in Monrovia talks of landlords throwing out tenants because they were professional ETU health workers. Other challenges are debilitating health as a result of trauma; and prospects of skin and lung cancer due to regular usage of the principal decontaminant chlorine.

Adequate compensation; motivating incentives; improved workplace safety; and housing and transportation facilities are just some of the needs of the frontline ETU health workers.

Informs Christiane Wiskow, Sector Specialist, Health Services, International Labour Organization (ILO), “The ILO offices in Dakar [Senegal] and Abuja [Nigeria] are developing a workplace response plan to be coordinated with the other UN agencies on the ground.

“This response plan will aim at improving the occupational protection of health workers, and help employers and workers to be prepared and informed for responding to the crisis. … We are also working with Public Services International, the federation of public services unions, to coordinate our mutual work in the best interest of the health workers on the ground.”

In the meantime, nurse Joy, 31, taking a breather outside a white ETU tent in Monrovia sums it up, “Nurses continue to survive in Liberia by God’s grace.”

(Nurses names have been changed on request to protect identity.) - Women's Feature Service