The legendary ‘Pad Man’ created hundreds of women entrepreneurs with a combined turnover of Rs 250 crore

08-February-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 6

Unlike other entrepreneurs, Arunachalam Muruganantham likes to measure his success not by his company’s turnover or profit, but by the number of livelihoods he’s created since he started his business.

The now famous inventor of the low-cost sanitary napkin manufacturing machine, whose story - in a fictionalized version - has been made into a film, Pad Man, is happy his business model has created hundreds of rural women entrepreneurs whose combined annual turnover is estimated at Rs.250 crore.

|

|

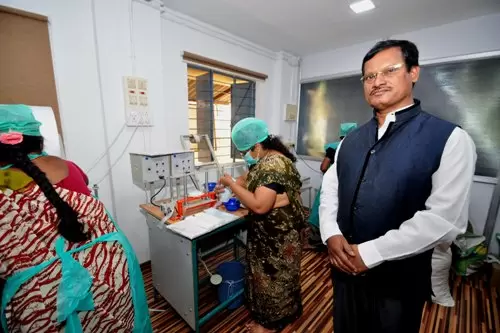

Muruganantham with the machine at the Employment Training Centre of an NGO in Coimbatore, where persons with autism and cerebral palsy along with their parents produce sanitary napkins (Photos: H K Rajashekar)

|

Having sold around 2400 machines till date – they were installed all over India from Leh to Kanyakumari, and in 17 other nations, including the US - he estimates that 24,000 women have got employment through his machines and 13 million women use their pads.

His pads are being sold for just Rs 2 per piece and women are said to be buying them in barter, exchanging onions or other local produce for their pads.

“I could have created a single brand and gone for the franchise model. But I chose to empower the rural women giving them total independence. That is why there are now 980 local brands with names in local languages, which brings the product closer to the village women.

“I could have made millions by building one brand and having a Kareena Kapoor to endorse it. But that is old model. I wanted to try something new.

|

“I did not want to make money, because there is no fun in it. If money can give all the joy, then why do people accumulate wealth and then start giving it away in the name of philanthropy,” says Muruganantham, 53, whom I first met in 2009 when he wasn’t yet an international figure.

When I met him that year at his workshop in Coimbatore - a 350 sq feet tin roofed shed, which had few machineries and even fewer workers - five years had gone by since he had developed the machine.

Jayaashree Industries, a proprietorship firm, had already sold about 100 machines to women’s groups across India. Members of the groups not only had a source of income, but had made local women use their sanitary pads as well.

Muruganantham told me even then he was not interested in amassing wealth. He said a private company offered him a blank cheque to acquire the patent rights of the machine, but he had rejected it outright.

He wished to make a social impact by creating more livelihoods and improving the menstrual hygiene of rural women.

Seven years later, his vision remains intact, though he is today a globe trotter and a much sought after speaker at B Schools and corporate meets.

|

|

Many sanitary napkin brands produced by women's groups using Muruganantham's machine have names in vernacular languages

|

He was listed in Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world in 2014 and has rubbed shoulders with the likes of US President Barack Obama, Microsoft founder Bill Gates, and Alibaba’s Jack Ma.

In January, the government of India chose him for Padma Shri award, the honour coming days after he received the news that the Confederation of Indian Industry had selected him as Indian Business Leader of the Year.

He has received prestigious awards from around the globe, but at his house in Coimbatore you will find none of it on display.

Muruganantham lives in a 500 sq ft rented first floor home at PN Pudur, where in one portion he has kept his fitness kits, sample packets of sanitary pads made by the women’s groups, and also his numerous awards inside a steel almirah.

“I don’t want to see them every day. It gives you a sense of accomplishment and makes you complacent. I want to be like my 8-year-old daughter, who wakes up like a butterfly every morning, fresh and full of energy,” he says.

But he lets us have a glimpse of the awards and citations, and spreads them on the floor giving us a photo op.

His wife Shanthi endorses his simple lifestyle, and feels that chasing money alone would not bring lasting happiness.

“We may not be making much profit, but we are still a zero debt company. When I meet CEOs of big companies, I mention this to them, and they usually respond by saying they need to check with their finance department on how much debt their company has,” he says, letting out a hearty laugh.

For someone who has created jobs for thousands of women, Muruganantham’s turnover is just around Rs. 2 crores. He has employed ten people, and they make about 12 machines every month.

The machines are custom made according to the requirements of the groups that place the order and priced differently.

.webp) |

|

Muruganantham has received several prestigious awards, but he does not like to flaunt them

|

“I am not into mass production. If someone wants to empower their widow sister we can make a machine for Rs.40,000. If three women wish to work together we can make one for Rs. 80,000.

“If you need a machine for a woman with one of her hands paralysed I can create a special machine for her. If we make a machine for more women to work on it, the price goes up, as would the production of pads.

“The price of a machine would range from Rs.40,000 to Rs. 3 lakh depending upon the number of livelihoods you want to create,” says Muruganantham, the son of a handloom weaver who has studied up to Class Ten in a government school.

His family was poor and as a young boy, he remembers hanging out with the shepherd boys in the fields.

“I used to marvel at the way the boys handled hundreds of sheep with the help of just one dog,” says the maverick social entrepreneur, who was at one time a steel fabricator.

It was after marriage when he found his wife using a dirty rag during her menses that he embarked on a mission to give her a cheap and clean sanitary pad, which he wanted to make himself.

His research started in 1999, took his time and savings for the next six years or so, and brought him to the brink of a divorce when his wife thought he had gone mad collecting the blood stained used pads of women.

For Muruganantham, it was part of his research testing his prototypes on women and constantly improvising on them. It took him a couple of years to realise that the absorbent in the pads was not ordinary cotton and that it was pine wood pulp, a raw material that had to be imported.

He also learned that one needed crores of rupees to set up a manufacturing plant for sanitary napkins. However, he did not let that information discourage him, but continued his research to develop a cheaper alternative.

|

|

Muruganantham has opted for a spartan lifestyle and lives in a small rented house in Coimbatore

|

“I must have spent lakhs of rupees on my research. I sold machineries in my steel fabrication unit one by one to fund my research. At one stage I was left with my welding machine, which I used to take on my two –wheeler to workplaces and do onsite jobs.

“I sold it eventually to raise money for transporting my prototype to IIT Madras for an innovation competition in 2006, which was a turning point in my life,” he recalls.

He won the first prize in the contest and soon with financial assistance of Rs. 15 lakh from IIT Madras and National Innovation Foundation, Ahmedabad, he set up his sanitary napkin manufacturing unit in Coimbatore.

Now, Muruganantham is all set to scale up his production without disturbing the basic business model.

“We are looking at a Rs.75 crore expansion plan. Investors are interested in joining hands, and part of the plan is to set up manufacturing units in three other places in India – Gujarat, Delhi and Kolkata – and one in Singapore, to reach out to the global market,” he reveals.

His firm will be converted into a private limited company and he plans to retain 61 per cent stakes in the company.

“I have told investors that they need to put social goals over profit. My aim is to create one million livelihoods for poor women and make 100 per cent of women in India use sanitary napkins (from the current 12 per cent level),” he asserts with his trademark confidence.

In the process, he says they would become a Rs.1000 crore company in three years time.

This Article is Part of the 'Amazing Entrepreneurs' Series

Updated on February 12, 2018

MORE AMAZING ENTREPRENEURS

VKC Mammed Koya, Founder, VKC Footwear

Chayaa Nanjappa, Founder Partner, Nectar Fresh

Dr. Nayana Patel, Medical Director, Akanksha Infertility Clinic