By honouring a throwaway promise, Kanta Chakraborty brought honour into the lives of 20 homeless girls

14-March-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 11

From the crack of dawn till late at night, for the past nine years, Kanta Chakraborty, a primary school teacher, has been the guardian angel to 20 homeless young girls at the Dum Dum railway station, taking care of their every need, empowering them for the future and filling their lives with hope.

“I have only one dream,” says Kanta, “that the girls live up to my expectations by achieving success and a respectable place in the society.”

|

|

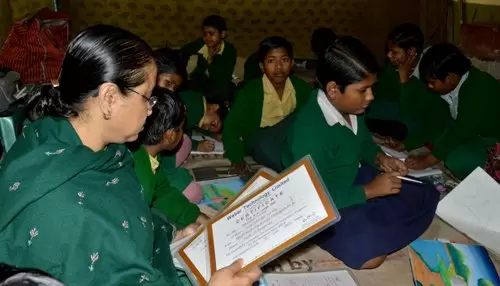

Some of the girls under Kanta's care were once addicted to sniffing adhesives, but came out of the addiction after undergoing counselling (Photo: Monirul Islam Mullick)

|

The large clock at Dum Dum railway station in Kolkata reads 4.30 a.m. The silence at the station is broken occasionally by the public address system, which has few listeners so early.

Unmindful of the wintry fog and cold, a woman in a sari is seen walking hurriedly to platform number one. She knocks at the Hawkers’ Union room there, glancing anxiously at her watch. “Hurry up!” she calls out.

“We are already late for the swimming class.” Her words are a wake-up alarm for the 20 girls, between four and 14 years, tucked cosily in the room. They soon queue up for the single washroom, to get ready for Didi to start off their day.

Didi came into their lives one ordinary morning in May 2007, when she was waiting to catch a metro train to her school in the city, Behala Shanti Sangha Shiksha Mandir.

“Two shabbily dressed girls, about six years old, approached me with a begging bowl in their hands,” she recalls. Kanta instantly asked them why they didn’t go to school. “Who will teach us?” the girls asked. Kanta said she could. Then she boarded the train, and forgot about her promise.

Two days later, when Kanta was back at the station, the two girls walked up to her and asked, “What happened? Why you didn’t come to teach us? You had promised.”

Their words haunted Kanta; she couldn’t sleep that night. Next morning, she discussed the incident with her husband Chandan Chakraborty, who works in a printing press. He said he would support her fully and even extend financial help.

The same evening, the couple went to the station and met the hawkers and railway officials there to seek their help in their plan to teach the girls at the railway station. Both groups were willing to help, but this was easier said than done.

|

|

The children, who study in nearby government schools, have been winning prizes in quizzes and sports competitions too.

|

“The girls were unkempt, wearing dirty clothes and had heads full of lice and injuries,” says Kanta. She took them home, about a kilometer from the station, for a bath.

Worse, the girls were victim to addictions such as sniffing adhesives, which is very common among railway-platform children. It took several days of counselling and strict discipline to get them off these habits.

The next challenge was finding the space for starting classes: The station was choc-a-bloc with passengers throughout the day. It was here that the Hawkers Union came to her rescue. They offered Kanta space outside their small Union Room on platform number one. But a major problem remained: the girls had no place to stay.

The hawkers union, once again, came forward, offering their office room for the girls to stay, while the union members slept on the platform. This has been the girls’ home ever since, a place for them, and for their clutch of clothes and belongings safe in a little almirah.

“Had it not been for their support, the school could have never started,” says Kanta. “Then we got a security guard to man the union gate at night.” The group that started with just five girls in 2007 has now grown to 20 girls. In 2009, Kanta registered this shelter as the Nihar Kanya Rehabilitation Centre after the name of her grandmother Niharkana Devi.

Kanta’s day starts at 4 a.m., as she makes her way to Dum Dum station. Accompanied by her two helpers, she takes the girls to a swimming club near to the station. After breakfast they sit down to study and also do some extra-curricular activities till 9 a.m. Soon after, they head for their schools.

“We have tied up with different government schools in the area,” says Kanta, “which charge a nominal fee.” By the time the girls get back from school, Kanta has also returned from her job. Post snacks, the girls begin their tuition classes that go on till 8 p.m.

Initially, Kanta used to bring home-cooked food for the girls, but people began to donate to her cause after coming to know about it in media reports and now she has hired a caterer to provide their meals.

|

|

Children trying their hand in drawing

|

Even after the last meal is served, Kanta’s day is not over. She ensures that the girls are in their beds in the room by 9 p.m. and the guard is in duty outside.

Come what may, the same routine is followed through the year. Kanta protects the 20 girls under her wings like a mother, dedicating her life to their upbringing and education - from paying their school fees to providing books, food and clothing.

Seeing her dedication, some people have joined in her noble cause and help her with the Rs 20,000 she needs per month to take care of all the expenses for the girls. Kanta uses a part of her salary for this.

A local doctor does a free weekly health check-up of the girls. An art teacher, Narayan Das, offers free drawing classes to the girls. “I was impressed to see her (Kanta) working diligently for the poor girls and decided to give her whatever support I can,” he says.

However, it is the girls themselves that have been Kanta’s greatest reward. They have been winning laurels in studies, quizzes and sports competitions.

Like Guriya Mahato, who is taking her Madhyamik (Class X) exams this year, is a meritorious students and often stands first in class. “I am indebted to Didi for all she has done for us,” Guriya says.

.webp) |

|

Kanta has plans to offer vocational training in tailoring and other skills for the girls

|

“Without her, we would have continued to loiter on the platform and be vulnerable to all sorts of bad things.”

The railway clock sounds 9 p.m. when Kanta leaves the platform after the girls fall asleep. She has a few hours to rest before she is back at the station. She has been up on her feet for 19 hours, but her mind is still on her plans for the girls: she wants to start vocational training like sewing and tailoring for them.

She knows she can make it happen.

After all, her one throwaway promise transformed not only her life but those of twenty others.