Next, Saraf wants to take his low-cost high-quality medical care service outside Kolkata

18-June-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 25

Following an oath he took on his brother’s funeral pyre, Deo Kumar Saraf has gone on to give a fresh lease of life to many thousands of people by building a chain of hospitals to offer quality medical care to the poor at the lowest possible costs.

Deo Kumar Saraf, now 73, the founder of the Anandalok group of hospitals in Kolkata, is not a doctor, but he has suffered every heartbreak of scarcity.

|

|

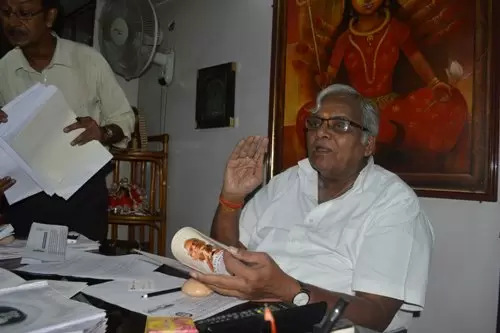

Deo Kumar Saraf (right), the founder of Anandalok group of hospitals, started a small dispensary first at an unused garage with four staff members in 1981 in the Lake Town area of Kolkata (Photos: Monirul Islam Mullick)

|

That’s why this graduate in Commerce offers the destitute the best of treatments at the most affordable rates, often even cheaper than the state government’s subsidised medical care.

His hospitals provide bypass heart surgeries at Rs 85,000 inclusive of all expenses, which is less than one-fourth of the amount private hospitals charge. More than 10,000 poor patients have availed of these surgeries.

Moreover, the heart angiography, for which other hospitals charge Rs 30,000, is done at just Rs 9,000 at Anandalok hospitals. Patients pay just Rs 75 as the daily bed fee.

Born of personal tragedy and public good, Anandalok started in an unused garage as a dispensary with basic treatment facilities and four staff members in 1981 in the Lake Town area of Kolkata.

Now it is a full-fledged chain of seven hospitals with over 1,500 employees.

Saraf, lovingly called Dada (‘elder brother’ in Bengali) by his staff, was born in a middle-class family at Bhawanipur in south Kolkata, the eldest of four siblings, with a younger brother and two sisters.

His childhood was darkened by his father’s domestic violence. “We were financially dependent on him and so bore everything silently,” he recalls, at his 250-bedded hospital and Anandalok HQ in Salt Lake in eastern Kolkata.

He was just 15 when his mother Gopi Devi walked out of her husband’s home with her children and moved to a relative’s house in Burrabazar in Kolkata.

|

|

Patients pay just Rs 75 as the daily bed fee at Anandalok

|

In 1959, when just 16, Saraf took up the job of an accounts assistant with a private company at a monthly payment of Rs 250.

“Soon after, we rented a small flat for Rs 125 monthly,” he says, recounting his days of struggle. “The bus fare from home to office was 20 paise, but I walked 11 kilometres each way to save even that, as I was my family’s sole breadwinner.”

Came 1963, a cruel and unforgiving year. His younger brother Krishna Kumar, only 18, fell sick. “The private hospital we admitted him into asked for two units of blood, costing around Rs 60,” he recalls. “It was a big amount for me then. I could not arrange it.”

Young Krishna died and Saraf was shattered. He swore on his brother’s funeral pyre that, if he could help it, no one would ever die of poverty like his brother.

“I swore that I would work to ensure that poor people get the best healthcare facilities at the minimum cost,” he says.

For the next 18 years, Saraf had many responsibilities, looking after his mother, wife, and two daughters on the monthly income of Rs 5,000 he earned from his business of supplying building materials, which he had started in 1960.

But he hadn’t forgotten the vow he had to fulfil.

“I kept asking people to donate space and money to start a healthcare unit, but no one came forward.”

|

|

Saraf collected alms from morning walkers using this very earthen container he is holding to start his first dispensary in Kolkata

|

His pleas were finally answered in 1981 when B.R. Gupta, the then chief secretary of the West Bengal government, heard of him through acquaintances and offered the use of a garage of around 500 square feet to set up a dispensary in Lake Town.

The dispensary started on July 11, 1981to cater to the three core medical problems of lower- and middle-class patients - pediatrics, eye (including spectacles) and TB.

They offered spectacles for only Rs 10, and expensive T.B. medicines at just Rs two for a pack for seven days.

“We had a monthly expenditure of Rs 3,000 for running the dispensary,” says Saraf. “I started giving tuitions to primary school children to fund it. I sought alms from morning walkers during my walk, and accepted whatever they offered, even a rupee or two.”

As his noble cause came to be known through media and word-of-mouth, the state government took note and in 1982 the then Chief Minister Jyoti Basu called him to Writers Building, the state government’s headquarters.

“He offered me around 4.5 cottah (3,200 square feet) of land in Salt Lake at a lease of rupee one, asking me to set up a healthcare facility for poor people,” reveals Saraf.

But construction required funds, so nothing moved for the next two years. “Mr Basu was upset at the delay and asked to see me again,” says Saraf.

Fortunately, at the Chief Minister’s office, a businessman had come to donate rupees one lakh to the state government welfare fund. “The Chief Minister asked him to donate the money to me instead,” Saraf says.

|

|

A humble man, for many years Saraf wore clothes stitched from the discarded bedsheets from his hospitals

|

And so it was that in 1984, a sixteen-bedded hospital with an Intensive Coronary Care Unit (ICCU) came up in the Salt Lake area at the cost of Rs 15 lakh, which included donations and around Rs 2.5 lakh from the sale of the ornaments of Saraf’s mother – she sold them to help realize her son’s dream.

In 1988 a patient suffering a heart ailment stayed at the hospital for 17 days. “He was so surprised to see that he was charged only Rs 1,700 hundred that he offered us around 4 cottahs (2,880 square feet) of land in Salt Lake,” says Saraf.

This is how the second 24-bed ICCU expansion came up in the Salt Lake Anandalok hospital in 1993.

At present, Anandalok has a chain of hospitals and diagnostic centres hospitals that include four in Salt Lake with a capacity of 350 beds in all; a 15-bedded one in Bhaduria off Barasat, around 40 km from Kolkata; a 200-bed facility in Ranigunj of Burdwan district, around 200 kilometers from Kolkata; an eye specialty centre at Bhawanipur; and another 16-bed hospital in Chakulia in Jharkhand.

Unchanged by time and fortune, Saraf recalls a telling incident. “I once attended a wedding of someone from the family of Mr B.K. Birla, the renowned industrialist. I was wearing my white clothes, a bit shabby after the day’s work.

“Nobody talked to me till Mr Birla came and shook my hand. People then surrounded me after coming to know of my work.”

For nine years Saraf wore clothes stitched from the discarded bedsheets from his hospitals. “I have tried to live a life of humility despite making money,” he says.

The group achieves a turnover of around Rs 50 crores annually and surprisingly, in spite of the low pricing of their treatment, makes a decent profit. In 2015-16, they had made a profit of Rs 11 crore.

|

|

An average of five bypass surgeries are done every day at Anandalok hospitals in Salt Lake and Ranigunj

|

Saraf has reasons to be unhappy with corporate hospitals. “They are fleecing people. We carry out the same surgeries with the latest technology at such a low rate and still make a profit.

“For instance, we earn around Rs three to four thousand in a bypass surgery after deducting all expenses,” he says, adding that around five surgeries are done every day in his hospitals in Salt Lake and Ranigunj.

Saraf, Trustee of the Anandalok Trust, is a philanthropic force and the subject of more than a dozen books.

The Anandalok Trust has constructed nearly 300 tubewells in many districts of West Bengal and thousands of pucca houses since 2006. Besides, it has also set up 29 libraries for poor students in rural areas since 1995 and helped conduct community marriages of more than a thousand couples since 2006.

Not one to rest, Saraf’s next mission is to replicate his low-cost high-quality medical care service in other parts of the country so that the oath he took more than 50 years ago can embrace more and more poor people.