Despite poor rains, people in the desert region of Rajasthan have water, thanks to an old system

26-January-2013

Vol 4 | Issue 4

Despite a drought-like situation across Rajasthan this year, farmers of a small village on the edge of the Thar Desert reaped good harvest from their fruit orchards. They are growing vegetables this winter.

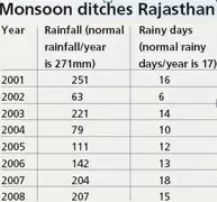

Just five years ago, residents of Khidrat struggled to arrange drinking water, let alone water for irrigation. Due to scanty rainfall (see table), groundwater was not only dipping, it had turned brackish. Even deep borewells would yield saline water. Every day, women and children would travel several kilometres to fetch drinking water.

|

|

Beri is a pitcher-shaped structure that catches rainwater and stores it (Courtesy: Gravis)

|

Those who could afford bought tanker water, which cost between 12 and 15 paisa a litre, depending on the distance and season. On an average, a family spent half of their income—more than Rs 1,250 a month—on buying clean water.

“This was strange. For hundreds of years, people in this region had coped successfully with the harsh climate. They had a rich history of rainwater harvesting and groundwater conservation,” says Rajendra Kumar, programme coordinator at Gramin Vikas Vigyan Samiti (GRAVIS).

The non-profit empowers communities in the desert. But the tradition had faded from their memory with the introduction of borewells in the late 1970s, and a few years later, with the Rajiv Gandhi Lift Canal that assured water at doorstep.

A few villages, including Khidrat, however, did not benefit from the canal. The government assured water supply to these upstream villages through tankers. What was provided for free in the beginning soon became a paid service. “We had always depended on barter system for our needs. But with tanker water came the need for cash,” says Ram Kishan, a resident. People in Khidrat and adjacent villages abandoned agriculture and livestock rearing and became labourers to earn cash.

“There was an urgent need to revive beris, a percolation well traditionally used to catch rainwater and store it,” says Kumar. The village had 34 beris, but all of them were defunct. In 2006 GRAVIS, with the help of Regional Housing Development Centre of Jai Narain Vyas Jodhpur University, revived the beris and began installing new beris.

|

|

Source: IMD, Rajasthan water resource department, Rajasthan Government

|

A beri is essentially a pitcher–shaped shallow well. It is about half a metre wide at the top and three to four metres wide at the bottom. The spot is strategically selected so that the percolated rainwater gets channelized towards the well.

While setting up a beri, people stop digging once they encounter a layer of clay or gypsum. These layers prevent further percolation of the stored rainwater, while the narrow mouth prevents loss through evaporation. Beris can hold up to 500,000 liters of water, sufficient to meet the needs of 10 families for a year.

People build raised concrete platform and cover it with a slab to prevent dust and surface runoff contamination. Depending on the size and structure, a beri costs between Rs 3,000 and Rs 15,000. When calculated, the cost of beri water comes to less than a paisa per litre, says Shrikant Bhardwaj, area coordinator of GRAVIS. The non-profit has so far built and revived 155 beris in Khidrat. About 90 per cent families of the village drink beri water.

The effort has begun showing results. Mangi Laal, who boasts of owning the largest beri in Khidrat, says, “I dug it with the help of my brother and kids. All it took was two bags of cement, sand, a lid and two months of labour,” he adds. Dug to meet drinking water needs of the family, Laal’s beri holds enough water to irrigate his farm. Last year, he grew millets, pulses, watermelon and cucumber and earned Rs 7,000.

By arrangement with Down to Earth