Kerala’s rural areas have turned around, economically and socially, thanks to women

05-October-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 40

When Syeda Hameed and Gunjan Veda ventured into rural Kerala, they discovered that villages in this progressive southern state did not look like villages at all! All the typical features – fields, hand pumps, ponds, thatched houses, stray animals – had been replaced by glitzy billboards and pucca homes painted in bright hues. Then, when they entered the Kanjikuzhy block panchayat in Alleppey, instead of the ‘MPs’ and ‘SPs’ – ‘mukhiya patis’ and ‘sarpanch patis’ – who usually ran the show in the northern plains, they were greeted by a forceful woman block pradhan, Jalaja Chandran. Not only did she know her panchayat well, she carried her charge with confidence. Rural Alleppey was full of surprises. But not so long ago, it was famine-affected and illiteracy was rampant as was unemployment. What caused the turnaround? Read on..

|

|

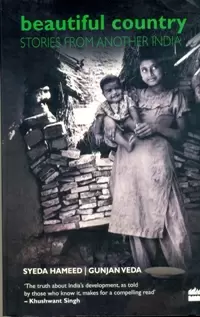

In Kanjikuzhy block panchayat in Alleppey, Kerala, block pradhan, Jalaja Chandran (extreme right) carried her charge with confidence (Photo: WFS)

|

From the airport we headed straight towards Alleppey. Like many towns and cities across the country, Alleppey has now reverted to its original name, Alappuzha. In Malayalam, ‘alla’ means ‘deep’ and ‘puzha’ means ‘river’.

What brought us to this district, famous for its criss-crossing rivulets and backwaters, were the three lakh women engaged in various coir related activities. In 2007, Alleppey coir was registered under the GI (Geographical Indication of Goods) Act.

As the car sped towards Alleppey, we passed Ernakulam. Rows of upmarket restaurants and shops lined the road. This time, the hoardings featured Kerala girls in Delhi-style salwar-kameez suits.

Not a single advertisement of white-and-gold Kairali sari, which is a must for every Malayali bride was to be seen. As we passed the city, we looked in disbelief at what was rural Kerala – a continuum of densely packed habitations.

These villages did not look like villages at all. The typical features of Indian villages – fields, hand pumps, ponds, thatched houses, stray animals – were missing. All the houses were pucca; many were painted in bright pinks, purples and oranges. It was difficult to make out where one village ended and the next began. Kerala seemed an uninterrupted urban agglomeration.

Finally, we entered the Kanjikuzhy block panchayat office which was located on the main road. Four women in silk saris with oiled and loosely plaited thick black hair greeted us.

A young woman came forward and introduced herself as Jalaja Chandran, block pradhan. The red bindi on her forehead was thinly lined with white sandalwood.

‘Kanjikuzhy block covers five villages and one town and has a population of 1.61 lakh people. Our block has 2,000 SHGs (Self-Help Groups) which have a turnover of Rs 2 crore per month.’ Jalaja spoke with quiet confidence.

‘Men work on the manufacturing side of the coir industry, and earn between Rs 100-150 every day. Women are the primary workers – cultivators and yarn spinners; they earn between Rs 40-60 a day.’

We listened intently to this forceful young woman. Women panchayat heads are no longer an uncommon sight in India. Yet, be it the salwar-wearing sarpanch of Punjab and Haryana or the ghoonghat-clad (veiled) sarpanch of villages across Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, often the woman is little more than a token.

The plains of northern India are full of ‘MPs’ and ‘SPs’ – mukhiya patis and sarpanch patis – who run the show with élan. In the past we had met many a woman sarpach who did not express a single opinion. Every question directed at them was fielded by the husband or the son.

Jalaja was different. Not only did she know her panchayat well, she carried her charge with confidence. For us, she epitomized the usefulness of women’s leadership in the primary sector. …

That night, Thomas Issac, Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from this area, later to become the finance minister of Kerala, joined us for a simple meal at the guest house.

Hearing of our experiences, he smiled. ‘Would you believe how backward this area was? At one time Kanjikuzhy had become famine-affected. Malnutrition levels were high, illiteracy was rampant as was unemployment. Its sandy soils did not allow much cultivation.

‘Then we decided to pursue education, simultaneously people started vegetable gardens and coir work. Prosperity followed. Look at us now. We are the best panchayat in the state.’

He went onto explain the success of Kerala’s Panchayati Raj system. Beginning in 1997, the state began extensive training for panchayat members. ‘Every year, surveys were carried out, needs assessed, sorted and prioritized. Thereafter, project proposals were prepared and discussed.’

From him we learnt other things about the state. Forty per cent of Kerala families rely on remittances from the Gulf; the people have enough money to spend. Hence the excessive displays of flamboyant consumer advertisements.

The next morning, Jalaja took us to the new building of the food processing centre, established by the Kanjikuzhy panchayat. Sparkling floors, neat, clean kitchen, women wearing gloves and aprons – everything about the centre was orderly.

On the stone kitchen counter, neat rows of bottles contained pickles made from bitter gourd, mango, ginger, garlic, lime, amla and asparagus.

|

It was a hygienic, appetizing and affordable array. ‘We make twenty kg of jams and squashes every day. Our women work from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and earn Rs 50 per day,’ Jalaja explained.

Accompanied by the other panchayat women – seven of Kanjikuzhy’s seventeen panchayat members are women – we moved to the village panchayat office. The famous Kudumbashree SHG programme was running here.

We saw women making umbrellas, chappals and bags. A two-fold umbrella sold for Rs 95 and a three-fold umbrella one for Rs 125! Women were bent over rows of sewing machines in small shops. The panchayat’s own computer centre had four desktops.

The women panchayat members spoke to us about their day-to-day work. Like Jalaja, they too were well versed about the PRIs. They ensured that most of the panchayat funds went into water supply, sanitation, agriculture, small industries, women and children.

They ran the schools, the anganwadis and the health centres. Local committees to supervise the anganwadis were active. For children’s daily meals, pulses, groundnuts, rice and occasionally eggs were locally procured. If children participated in sports, they got special food to ensure proper nourishment.

‘By the end of this year, every house in our village will have a latrine. We also have 90 per cent electrification,’ Jalaja said.

We were impressed by what we saw. There was no trace left of the poverty-ridden, educationally backward place which had been described by Thomas Issac the previous night.

(Excerpted from Beautiful Country – Stories From Another India By Syeda Hameed and Gunjan Veda; Published by Harper Collins) - Women's Feature Service