Born to landless farmers and raised in poverty, he built a Rs 3,600 crore company from scratch

24-October-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 43

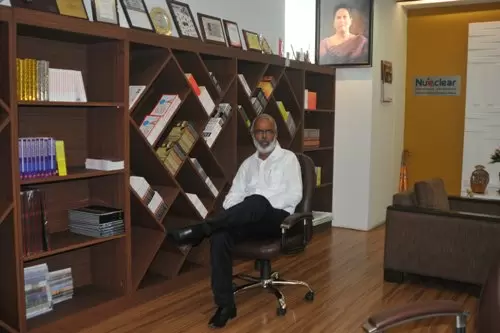

Arokiaswamy Velumani, 57, Chairman of Thyrocare Technologies Limited, currently valued at Rs 3,600 crore is a maverick entrepreneur.

He does not follow established practices or conventional wisdom to run his business. To give you an example, while almost everyone else places a premium on experience while recruiting employees, as a rule he employs only freshers in his company.

|

|

A Velumani, Chairman of Thyrocare Technologies Limited, hails from a village near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu (Photos: H K Rajashekar)

|

“I have about 1,000 employees. For nearly all of them I am the first employer. Just two per cent of my employees have some prior work experience,” says Velumani, sitting in his spacious cabin on the fifth floor of their six-storey corporate office in Navi Mumbai.

He adds that the mean employee age at Thyrocare is 25 years and the mean salary is Rs. 2.70 lakh per annum. The company achieved a turnover of Rs 235 crore in 2015-16.

In April, Thyrocare took the Indian bourses by storm when its initial public offering (IPO) was oversubscribed 73 times.

Thyrocare has 1,200 franchised centres across the country, where blood and serum samples are collected directly from patients and also from hospitals in the vicinity. These are then airlifted to their fully automated laboratory in Mumbai for testing.

Thyrocare has 1,200 franchised centres across the country, where blood and serum samples are collected directly from patients and also from hospitals in the vicinity. These are then airlifted to their fully automated laboratory in Mumbai for testing.

“We have 10 per cent of the market share in thyroid testing,” says Velumani.

A first generation entrepreneur, Velumani grew up in penury in a village near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu and worked as a kid in agriculture fields after school hours and during holidays to support his family.

His parents were landless farmers and cultivated crops on leased land, but their earnings were meagre to even meet the basic needs of their four children. Velumani was the eldest child and he had two younger brothers and a sister.

“In a pyramid of ten slices, I was in the bottommost slice. Now I am on the topmost slice. Those days I had no money, too much of time. Today, I have too much of money and no time.

“Those days I had too much hunger, but no food. Today, I have too much food and no hunger,” he says, rather philosophically.

Velumani is a chronic optimist and he likes to see the glass half-full at all times - in spite of his impoverished childhood that he “vividly” remembers.

|

|

Dr Velumani at his corporate office in Navi Mumbai

|

“I attended the panchayat union school till Class 5 with a slate in one hand and a plate in another, since I took mid-day meals (a government project for poor children) at the school.

“I remember going to school many days wearing only my shorts, because I would have given the only shirt I had for washing after wearing it for two or three days.

“I was the only student who did not get the group photo in Class 11, because I could not pay Rs 2 for the photo,” he says, with remarkable candour.

But the diehard optimist says he was richer than many others. “I had 60 meals a month, but there were children who didn’t have even 30 meals a month. They were poorer than me. That’s how I look at life,” says Velumani.

He describes all those difficult childhood experiences as “the luxury of poverty” – an expression he would keep repeating at regular intervals during our conversation.

The climb from the bottom of the pyramid to the top started way back in 1978 when he got his first job as a chemist at Gemini Capsules, a tablet manufacturing company in Coimbatore, for a monthly salary of Rs 150.

A chemistry graduate from Ramakrishna Mission Vidyalaya in Coimbatore, he says he studied chemistry hoping to get a job at South India Viscose, a rayon manufacturing company that has been shut down now, but which used to be one of the biggest factories in the Coimbatore region then.

“Viscose employees got 40 per cent of their salary as annual bonus and that was a big attraction for me. But I didn’t get a job there since I didn’t have experience. Many other companies too rejected me for the same reason – lack of experience,” recalls Velumani.

In hindsight, he believes it was all for good. “Nobody gave me even a clerical job. Fortunately, the capsule company where I got my first job also closed down within four years. Otherwise, who knows, I might have got stuck there,” he remarks.

|

|

The fully automated laboratory in Mumbai receives around 50,000 samples daily for testing

|

At 23, he had an opportunity to look out for a job again, and this time he applied for the post of a scientific assistant at Bhaba Atomic Research Centre (BARC) in Mumbai.

He visited Mumbai twice, first to attend the interview, and then for the medical examination, before he got the job in 1982.

“For a man living in penury, a government job with a salary of Rs 880 was a luxury. I could support my whole family with my income,” he says.

Four years later he got married to Sumathi, who was employed at State Bank of India, and who would become the apple of his eye.

While working at BARC he did his post-graduation and also completed his doctorate in thyroid biochemistry through a collaborative programme that BARC had with University of Mumbai.

In 1995, nearly 15 years after joining BARC, Velumani felt life had become too cosy and that he had to do something challenging.

|

|

Dr Velumanistarted Thyrocare in 1995 from a 200 sq ft rented garage at Byculla in South Mumbai

|

“When I quit my job everyone in my family wept. But my wife supported my decision. She too left her job and started assisting me in my business.”

“Together we were earning around Rs 10,000 per month. We used to spend around Rs 2,000 and save Rs 8,000 every month. We had Rs 2.90 lakh in our savings account when we quit our jobs. I knew that my family could live for 100 months with that money.”

“We lived frugally. Frugal people are not misers. They only spend for themselves. Stupid people spend because their neighbours are watching them. If you are frugal you are a king, if not you are a slave,” says Velumani.

He started Thyrocare in 1995 with his PF (Provident Fund) money of Rs 1 lakh from a 200 sq ft rented garage at Byculla in South Mumbai.

He operated on a simple business model, which he has just scaled up over the years.

|

|

Dr Velumani's children, Amruta and Anand are directors in the company

|

“Laboratories doing thyroid tests were struggling, because there were not many orders. I took a machine from a lab. That machine was working for only one hour and the rest of the time it was idle.

“I told the person I would do his tests free of cost for five years. That machine can do 300 samples a day.

“I did 50 samples for him free of charge and got orders for another 250 from the public. I kept adding one machine after another. In no time we acquired 10 machines and were doing about 3,000 samples daily,” says Velumani.

He would personally go and canvass for orders from labs and hospitals. The labs would call his office landline and inform when the samples were ready for collection. His wife would take the calls and convey it to Velumani whenever he called from a PCO.

“I would travel from one part of the city to another to collect the samples. I always took the suburban train for longer distances and just walked to the labs from the station, irrespective of the distance.

|

|

Dr Velumani's brother, A Sundararaju, is Chief Financial Officer at Thyrocare

|

“That’s the luxury of poverty. I had walked long distances back in my village and it was nothing new for me,” he says.

As the number of samples grew in size, he expanded the business and set up franchisees across the country. By 1998, they had 15 employees on the rolls and achieved a turnover of Rs one crore.

“We operate on very low margins. We charge just Rs. 250 for thyroid testing. I take Rs 100 and my franchisee takes Rs 150. The market rate for the test is Rs 500, though bigger hospitals charge around Rs 1,500 or even more,” he says.

Besides thyroid testing, Thyrocare has diversified into other areas of health diagnostics and does diabetes, arthritis and a range of other tests as well.

They receive around 50,000 samples daily, out of which around 80 per cent are for thyroid testing.

Velumani who has never lost in business suffered his greatest loss in life when his wife died due to pancreatic cancer earlier this year.

“You were an unending stamina pack, kept flying like a honey bee from floor to floor, building to building, table to table – touching thousands of people in and around Thyrocare with your smiles, files and mails,” writes Velumani, paying glowing tributes to his wife in the editorial of Health Screen, a monthly magazine published by the company.

Velumani holds 65 per cent shares in the company, 20 per cent is held by the general public and 15 per cent is with private equity.

His brother, A Sundararaju, and two children, Anand, 27, and daughter Amruta, 25, are actively involved in the affairs of the company as directors.

You might also like

Starting with a salary of Rs 650, he went on to build a Rs 1,500 crore valued company