Indian democracy and secularism will not fall despite all past setbacks

01-September-2011

Vol 2 | Issue 35

India in crisis is everyday’s story unceasingly told. The story that often gets short shrift is the story of our perpetual mutiny against those crises.

India almost teases miracles in the way it withstands or surmounts the many tides - chronic and extant - that besiege it. And in doing so it probably leaves most Indians confounded.

Until quite recently, Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul wrote only darkly about India, and most of what he had to say was prescient.

|

|

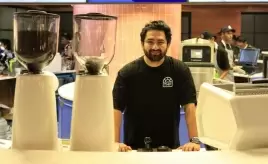

In conversation: The author (right) with historian Ramachandra Guha (Photo by S Radhakrishna)

|

M. J. Akbar’s India: The Siege Within was written in a volatile moment two decades ago when India seemed about to crack – Sikh separatism in Punjab, the renewed clamour for self-determination in Kashmir, the spew of religious fundamentalism, Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the consequent street mayhem.

It passed. And more came and passed. The turbulence of Mandir and Mandal, Rajiv’s bloody end, the Babri demolition, the Gujarat carnage, tsunami and quake, flood and famine, terror sharking from dateline to dateline, finally barging ashore in Mumbai to catch the nation by the jugular.

But India has a way of shrugging off setbacks and lumbering on, a quality that earned the nation just concessions in Naipaul’s later work.

And Akbar might want to update his pulsating report of alarm from the trenches with calmer analysis.

As Ramchandra Guha said of the country’s coming of age in ‘India After Gandhi’, “Secessionist movements are active here and there, but there is no longer any fear that India will follow the former Yugoslavia and break up into a dozen fratricidal parts. The powers of the state are sometimes grossly abused, but no one seriously thinks that India will emulate neighbouring Pakistan.”

At the heart of the country’s endurance against odds, perhaps, lies the liberal–democratic ethic wrought deep into the nation’s political consciousness during the Nehru era – so deep that his daughter Indira was shamed into calling elections within two years of declaring the Emergency. She was cast out in the 1977 elections, but rode back to power on a huge mandate in 1980. Indians felt, justifiably, that their mammoth, often unwieldy country was fairly a creature of their will.

Indians are wont to dispose of emergencies, big ‘E’ or small. Neither the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 nor the slaughter of Muslims in Gujarat a decade later, has driven the country’s most populous minority east or west into Bangladesh or Pakistan.

Balasaheb Thackeray is a virulent, Hitler-loving bigot but his appeal remains contained within a precinct of Mumbai. Secession remains a live cry in India’s North East and in Kashmir, but both sets of separatists are in some form of dialogue with the government, even though elements haven’t forsaken arms.

India’s problems are manifold. Primary education and healthcare are still widely unavailable. Large swathes of this nuclear-power nation still have no access to water or electricity. Caste-based discrimination remains rampant enough for leaders to create militant political constituencies out of those that consider themselves victimised.

To ignore any of India’s many new mutinies would be to court ugly surprises. The slow burn of Naxalism, or armed ultra-leftwing rebellion, along the country’s impoverished border with Nepal probably holds in store many more terrible lessons about the pitfalls of iniquitous growth.

Inequality is the key problem. People are trying to discover ways of securing their rightful share in what they are being told is a prosperous place; they are impatient and their frustration could increasingly lead them to extra-democratic resorts, as actions of caste-rights groups like the Gujars of Rajasthan, or rising get-rich-quick urban crime, might suggest.

The Anna Hazare-led upsurge, again, is a symptom of the assertion of popular frustration and will.

And India, it can be said with little doubt, will emerge from the current crisis richer and better equipped to handle its many ailments.

India cannot have been the story of negatives alone. India is what quietly happens between the bad and the good -- a country living and prospering in its few unbroken, and largely unnoticed, emancipated practices: universal adult suffrage; uninterrupted democracy (barring the nineteen-month aberration of the Emergency which Indira Gandhi voluntarily corrected); justiciable fundamental and liberal rights.

India is destined to glory in her divides, that’s what makes her a mosaic rather than a monolith. The country, time and again, has affirmed the larger faiths Indians have imbued her with; in many ineffable ways, the sum of their common benefits has far outweighed their cumulated contradictions.

The late John Kenneth Galbraith, John Kennedy’s ambassador to India in the formative and critical early 1960s, was bemused enough by the contrary continuum he witnessed to call India a functioning anarchy.

Half a century later, that still sounds apt.

The author is Roving Editor, The Telegraph